By Haina Wang, PhD, guest researcher and previous post doc fellow at the Department of Biological Sciences.

The original research article was published in Communications Biology in 2025

The Viruses That May Have Helped Shape Eukaryotic Chromatin

In 2020, wearing a mask, I flew to Norway and arrived at the University of Bergen to start my research on marine giant viruses.

When I first met my supervisor, Professor Ruth-Anne Sandaa, she walked with me up and down the corridor and then pointed to an office at the very end:

“Have you heard of the kill-the-winner hypothesis? It was proposed by this guy.”

Only then did I finally connect the surname I had seen so many times in the literature with the full name on the office door. The professor himself had retired, but he would still come back around Easter and other important holidays to sit in the meeting room with everyone, eating and drinking together.

Two “star” viruses that were supposed to be boring

The first project I took over was to analyse the genomes of two giant viruses: HeV-RF02 and PkV-RF02.

Giant viruses are a very flashy topic in virology because their existence challenges the traditional definition of a virus. Anything that can challenge the textbook tends to end up in the most prestigious journals.

My two viruses also looked like they had “star potential”. Their hosts are haptophyte algae, a group of widely distributed unicellular eukaryotic algae that contribute an estimated 30–50% of marine primary production. Some haptophytes are also notorious red-tide formers, such as Phaeocystis globosa. In the past decade, harmful algal blooms along the coast of Guangdong, in southern China, have most frequently and most extensively involved Phaeocystis globosa.

In reality, though, my two viruses were incredibly “boring”.

Their hosts are non-blooming species of haptophytes, species that do not form red tides. The basic parameters of these viruses, i.e. morphology, host range, one-step growth curves and so on, had already been published. The only thing that could really be called novel was their genomes, which also happened to be the hardest part to interpret.

At the time, like many early-career researchers in China, I was under strong pressure to publish in high-impact journals and their sister journals. The expectation was that I needed at least two such papers before I would be considered “successful enough” to return. These expectations became a kind of nightmare for me.

If I were a virus, what would I do?

Looking at genomes from the virus’s point of view

During my time in Norway, I had a very important collaborator: Professor Hiroyuki Ogata from Kyoto University. One of his major scientific contributions was helping to build and maintain the KEGG database. KEGG integrates a wide range of data and experimental results, and can show us metabolic pathways and signalling pathways at the scale of the whole organism. It is a very powerful resource.

Because of his influence, our initial analyses were all based on KEGG-related databases. But soon I realised that something was off.

When we analyse a genome, we first predict how many “genes” are encoded along the sequence. Then we compare those genes to the genes already stored in databases and, based on sequence similarity, we infer what each gene might be doing. This step is called annotation. From the annotation, we can get a first idea of what the virus is capable of.

Everyone does this, and for a long time it seemed perfectly fine.

But what are those annotations in the databases themselves based on?

They are based on previous research, and previous research has focused mainly on cellular organisms, especially humans. As a result, the “functions” and “pathways” we can look up are mostly framed from the host’s point of view, not the virus’s.

By the time I fully realised this, I had already gone through a full round of genome analysis for the two viruses. Each genome had about 500–600 genes, which means I had looked up more than twelve hundred genes. And then it hit me: our interpretation of these genes was implicitly assuming that each gene belonged to the host, and then guessing what it might be doing.

This works reasonably well for many kinds of analysis. But when you want to pick out and interpret the genes that govern virus–host interactions, this perspective can lead you badly astray.

So I started to go through each “gene” again, one by one, this time focusing on its protein domains, which are its secondary structural units.

In the absence of direct experimental evidence, I felt that domains were the most basic way of understanding a protein: short stretches of amino acids that form conserved structural and functional units. Using databases such as Pfam and InterPro, we can identify the type of each domain and what kind of biochemical reactions or biological processes it is involved in, based on the literature. That allows us to judge, with some confidence, what process the protein encoded by a given gene might participate in.

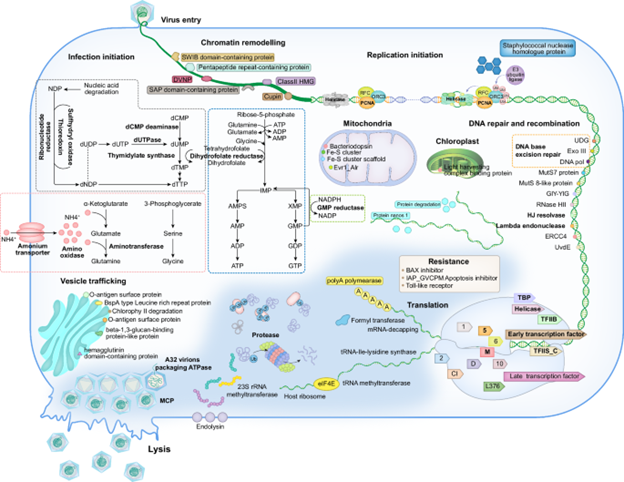

With this, our functional classification shifted: instead of using the usual categories like “cellular genetics and metabolism”, we began to organise the genes along the entire infection cycle of the virus.

In this way we built up a “possible picture” of how a giant virus infects a haptophyte cell.

Even without direct experimental proof, this “possible picture” gave us a new way of seeing the functions of giant viruses.

DVNPs: a missing piece of the evolutionary puzzle

While I was examining the domains in these viral “genes”, I noticed something odd.

One gene was annotated simply as a “hypothetical protein”, but it contained a fairly large domain labelled “DVNP-containing protein”. So I looked up DVNP, and stumbled onto a very interesting evolutionary story.

DVNP stands for dinoflagellate/viral nucleoprotein. Dinoflagellates are a group of planktonic microorganisms with rather abstract, even bizarre shapes. They have huge genomes, and scientists think they may have undergone genome enlargement at least twice, “eating” lots of DNA from other organisms and putting it to use for themselves.

Why does that matter?

There is a basic rule of thumb in biology: all eukaryotes use histones to package their chromosomal DNA. Dinoflagellates are the only known exception. They use a special kind of DNA-binding protein instead. When this protein was characterised, it turned out that it probably came from a virus.

But there was a mystery: those viruses do not infect dinoflagellates. So how did dinoflagellates acquire these genes and use them to replace histones in packaging their chromatin?

The DVNPs we found in our haptophyte viruses turned out to be a crucial clue.

When I presented this work at a conference in 2023 and mentioned DVNPs, Professor Ogata became very interested. He invited his PhD student, Lingjie, to search across all available databases. They found that DVNPs are widely present in two groups of marine giant viruses, i.e. Algavirales and Imitervirales, as well as in some dinoflagellates.

We collected these DVNP sequences and built a phylogenetic tree.

We were delighted, but not really surprised, to find that the DVNPs from dinoflagellates (the cellular DVNPs) were “rooted” firmly within the clade of Imitervirales viruses, right where our two viruses, HeV-RF02 and PkV-RF02, sit.

The tree was clean and elegant, and it strongly suggested that dinoflagellates had acquired their DVNPs from viruses in the Imitervirales group.

At that point, I asked a new, further question.

Dinoflagellates are eukaryotes, so they have a nucleus. The nucleus is surrounded by a nuclear envelope, perforated by nuclear pores, each guarded by a nuclear pore complex.

Even if a dinoflagellate acquired the DVNP gene from a virus and started to synthesise DVNP protein in the cytoplasm, how could that protein cross the nuclear pores and replace histones in the nucleus?

It would need a small sequence element called a nuclear localization signal (NLS).

I found a small piece of software that could predict NLSs, and ran it on all the DVNP sequences. Once again, we were both surprised and not surprised:

the positions of the predicted NLSs in DVNPs from Algavirales, Imitervirales and dinoflagellates were completely different.

This suggested that, after acquiring DVNP from Imitervirales viruses, dinoflagellates went through further evolutionary steps to gain new nuclear localization signals, which then allowed DVNPs to pass through the nuclear pores, enter the nucleus, and replace histones.

This would make dinoflagellates the only known eukaryotes that package their own chromatin with a virus-derived protein.

Horizontal gene transfer is very common in nature. But cases where viral genes move into eukaryotes and change their fundamental traits are still quite rare.

The DVNPs we found in these two haptophyte viruses provided a missing puzzle piece in the evolutionary story of dinoflagellates, helping to “close the loop”.

“That’s a different price.”

We first submitted this work to Nature Microbiology. The editor replied that horizontal gene transfer is a common phenomenon, but if we were willing to transfer the paper to Communications Biology, they would be happy to send it out for review.

By then I had already invested so much time and energy in these two viruses that I didn’t want a long, drawn-out struggle. I agreed.

About six weeks later, we received the reviewers’ comments. The main request was that we express DVNPs experimentally to test our hypothesis.

I wrote a very long response explaining why we could not do that.

But the loudest voice inside me was simply:

“That would be a different price.”

For a long time, I genuinely disliked these two viruses. I often regretted spending so much time on such “boring” viral genomes.

But the long journey reshaped how I understand viruses. It trained me to think in a new way:

If I were a virus, how would I survive?

That way of thinking will be very useful for my future work.

The viruses that made a Norwegian work overtime

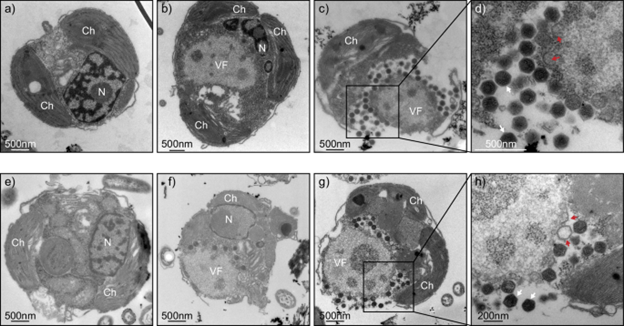

Finally, let me show you how these two viruses infect their host cells. I have always loved morphology.

The engineer who helped me prepare the samples and take the TEM images is Endy. She likes “my” viruses too. She would send me text messages while imaging them, or come in early to wait for me downstairs so she could start working on my samples.

Once, she even worked overtime because “the viruses just looked so funny” under the microscope, even though she was flying to Spain on holiday the very next day.

These are viruses that can make a Norwegian work overtime. Just thinking about that makes me rather proud.

For a long time, I have very complicated feelings towards everyone on the author list of that paper, even including myself. When our manuscript was accepted by Communications Biology and we received proof before publication, I received positive feedback from my colleagues, “great work””Congratulations”.

After the paper was finally published three months later, I sat down and carefully wrote a thank-you letter, sincerely thanking each author and colleague. Professor Ogata replied, sending me his congratulations and best wishes.

When I had just started working at the University of Bergen, I had a meeting with the dean, the faculty secretary and my supervisor. The Head of Department told me:

“Your task is to develop yourself. The tasks of your supervisor’s project are her own business. We hope that in the end you will publish papers as an independent corresponding author.”

Looking back on the whole process, I feel fairly satisfied with myself, my supervisor and my team.

I have done right by these viruses. Once, they could only be described. Now, they come with a plausible hypothesis about their role in evolution. That is already pretty good.

Later, I worked on more viruses, each of them fascinating in its own way.